What is to Be Done, FDP?

A few weeks ago, I published an analysis titled “Quo Vadis, German Liberalism?” that—somewhat unexpectedly—reached a wide audience. Naturally, that makes me happy … and yes, it strokes the ego. :)

But if we’re being honest, not much has happened since. Sure, there’s been interest in the piece, but a lot of it felt more like intellectual curiosity than serious strategic reflection. While many in the broader liberal ecosystem recognize that it’s five minutes to midnight, the FDP still seems trapped in a kind of fatalistic optimism best captured by an old Cologne saying: Et hätt noch immer jot jejange. In other words: “2029 will somehow work out.” After all, 1. FC Köln always manages to fight its way back into the Bundesliga.

And why not? It’s worked once before—so why shouldn’t it again? The problem begins when you ask: How, exactly? That’s when things go quiet. Very quiet.

Back then, the FDP had outstanding political talent: Christian Lindner wasn’t just charismatic and rhetorically brilliant—he also had a sharp instinct for timing and people. He brought in media heavyweights like Wolfgang Kubicki and Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann, and added a second row—Johannes Vogel, Konstantin Kuhle, Lukas Köhler—that was young, hungry, and experienced enough to be immediately effective.

Fast forward to 2025 and the picture looks dimmer: Christian Dürr, Nicole Büttner, Henning Höhne, Svenja Hahn, Florian Toncar. Many of them I know and personally admire—but I don’t think they'd hold it against me if I said: this isn’t quite the dream team we had back then. Add to that the fact that internal tensions and a dysfunctional party culture have burned through an entire generation of talent. That doesn’t help. And yes, rumors suggest that even assembling the current executive board was anything but smooth.

But even if we had another Lindner or Guido-level talent waiting in the wings—a political movement can’t build its future on the hope that every decade a new savior will appear. If liberalism only works when led by extraordinary individuals, it’s structurally dead as a political force. What we need isn’t a messiah but a well-thought-out strategy, a culture of experimentation, clear processes—and an organization that has the courage (and openness to outcome) to try new things. And survive failure. In short: a liberal culture.

One common critique of my first piece was that much of it was too abstract and philosophical. While that’s certainly on brand, I can, in fact, embrace the full scope of the dialectical method: theoretical and conceptual as well as practical and material.

So now, in the spirit of Lenin: Что делать? What is to be done, FDP?

§1—Against Blind Activism: Understanding Before Acting

In moments of crisis, people often panic and jump into action. We’ve all been there: relationship breaks down, and you immediately sign up for the gym. New life, new me. But without real introspection, this will only be performative. (Been there, done that.)

We quickly fall back into old habits—the very ones that block the transformation we so desperately need. Political parties are no different.

Now is not the time for the FDP to wallow in self-pity or lick its wounds. But it must take time to understand—very much in the Weberian sense. A new leadership team shouldn’t show up with a ready-made narrative and fixed answers, but with a willingness to work through why we are where we are.

That requires a clean and honest look at both external factors (paradigm changes, voter shifts, cultural dynamics) and internal ones (campaigns, structures, communication patterns).

And this can’t be confined to internal committees. Liberalism’s crisis needs to be addressed holistically—which means the base, thought leaders, and supporters all need to be systematically and analytically included. The FDP 2025+ project is inseparable from the Liberalism 2025+ project.

This cannot get stuck at the operational level. The neoliberal management reflex—have staff prepare slides, then let the executive pontificate—won’t cut it. This needs political leadership. But not via a commission. That only attracts people with too much time on their hands.

Instead, we need a process with intellectual rigor, internal weight, public relevance, and genuine political value. Because only from understanding comes real-world consequence.

We may not have a liberal Steve Bannon to orchestrate this process and build a strategic playbook—but we do have plenty of politically savvy minds in the wider liberal orbit. We need to bring them in now, and keep them close. They won’t help us from the private sector. We need people with a Weltanschauung—people willing and able to co-design Liberalism 2025+ holistically and metapolitically.

§2—New Political Aesthetic & Cultural Shift: Kill the Stale Vibe

Any real strategy process has to start with one question: How do we get members and supporters excited again?

In the past, the FDP tried to do that with regional conferences and new mission statements. I fear we’ll reflexively go down the same road again. But it won’t be enough. It wasn’t enough last time either. Strip out the brief “freedom bump” during COVID, and the party’s been stuck around 5% for years. So, that ain’t it.

Regional conferences, frankly, are relics. They come from an outdated organizational logic of the old West Germany: excessively proper, bureaucratic, and bourgeois—but also hierarchical, rigid, and utterly predictable. That whole vibe has to go. Party congresses aren’t forums of deliberation; they’re stages for self-promotion. Fine for MUN or debate clubs. But not serious politics. When I was IFLRY Secretary General, I deliberately kept this performative aspect of political discourse to a minimum.

Back to structure: Programmatically, the FDP is a liberal party. But structurally, it’s conservative—party congresses, district boards, proportionalist rituals. You can smell the dust: suits, procedural motions, formal address. It doesn’t feel like a start-up—it feels like a moldy antique shop.

This isn’t just unappealing—it’s out of time. And so is the language liberalism still uses. (More on that another day.) If you want to reach your audience, you need to speak like your audience. The FDP’s operating system—FDP95—needs a reboot.

Liberalism in the 21st century won’t thrive by updating policy positions alone. It needs a cultural reset—one that allows new positions to emerge organically from worldview and lived experience, not conference votes. Internally, we could afford to be raw, messy, and unprofessional. Ditch the formalities. Be cheeky, not polished. Host happenings, not party conventions. Act, don’t debate.

In other words: It’s all about the vibes. And the vibes need to change.

§3—Clear Roles, Clear Leadership

The new FDP leadership faces a heroic task: dragging liberalism out of the Bonn Republic and into 2020s Berlin. Neither the party’s current structures nor its voter base is built for that. Lol.

That kind of transformation only works if the leadership understands its roles—and its place. This isn’t classic committee work. (Let’s be real: a 4% party can’t afford a supervisory board mindset.) What’s needed is an operationally effective leadership team that can organize liberalism across the party and beyond.

That means assembling complementary roles:

- The Leader (or Doppelspitze): A face of renewal. Someone who can speak and think freedom in visionary terms. A figure who sparks energy in the public and within the party.

- The Fixer: The person who has the leader’s back and works the organization from the inside. It’s not enough to be strategic—this person needs to get their hands dirty.

- The Wonk: Deeply grounded in policy, respected for their expertise, tuned into societal conflict lines—and ideally with a forward-looking worldview.

- The Communicator: Media-savvy, poised, and present. More than that: someone who can translate the message of liberalism (and the FDP) into something that resonates—modern, compelling, and culturally fluent.

At its peak, the FDP had this setup: Lindner as Leader, Buschmann as Fixer, Vogel & co. as Policy Brains, Kubicki and MASZ as Communication Pros.

Right now, it’s unclear who could fill these roles. Either hidden talents need to be identified and elevated—or an entirely new personnel slate needs to be developed strategically.

Because without clear roles, the transformation won’t happen.

(Shoutout to Josef Lentsch, from whom I’ve learned a lot about party development over the years—and who’s written extensively about this kind of role architecture.)

§4—Talent Pipeline Over Staying Power

If it wasn’t clear yet: the top priority for the new leadership has to be strategic talent development. After getting kicked out of the Bundestag and torn apart by internal strife, the FDP has lost—or burned through—an entire generation of political talent almost overnight.

The party currently lacks the depth and capacity to campaign seriously. Many of the coming elections will have to be fought without parliamentary infrastructure and resources. Sure, the membership list says 70,000—but no one in the FDP (or anywhere else in politics, frankly) believes that’s enough to realistically re-enter parliament.

Worse still: in a committee system where endurance counts more than ideas, speed, or new perspectives, the party doesn’t just lack quantity—it lacks the kind of people who could lead a renewal.

So, what we need now is a full-blown offensive in political education—from onboarding formats for newcomers to high-level training for officeholders, thought leaders, and doers. And this has to be a leadership priority. It can’t be delegated to staff. Political leadership means: securing resources, building structures, and making talent a top priority.

Our sister parties are way ahead: NEOS with their NEOSLab, Democratic Alliance with their Young Leaders Program, VVD and D66 with their targeted training pipelines. That’s what we need. Not as a nice-to-have, but as institutional backbone.

The fact that the Friedrich Naumann Foundation is reportedly considering shutting down its Gummersbach training center is a political red flag. It shows that even within the liberal orbit, long-term priorities for organized liberalism’s survival are no longer universally shared. Anyone who thinks you can replace a shared, central learning space with webinars or regional scattershot programming is betraying the very idea of political community.

Building political talent isn’t just an operational necessity. It’s an ideological obligation.

And like so often, it starts at the top—with a new leadership culture. The party leadership can’t just preach this stuff—they have to live it. That means showing that political development doesn’t end with a parliamentary seat. They shouldn’t just give opening remarks—they should be in the room, learning too.

BTW, that might’ve spared us a few mistakes in the past.

§5—A New Strategic Self-Positioning

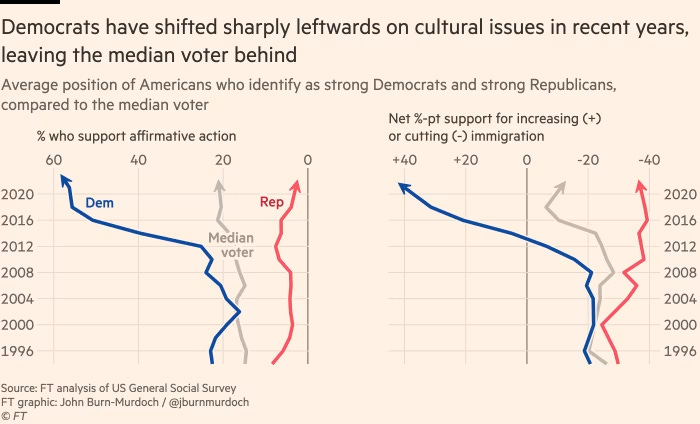

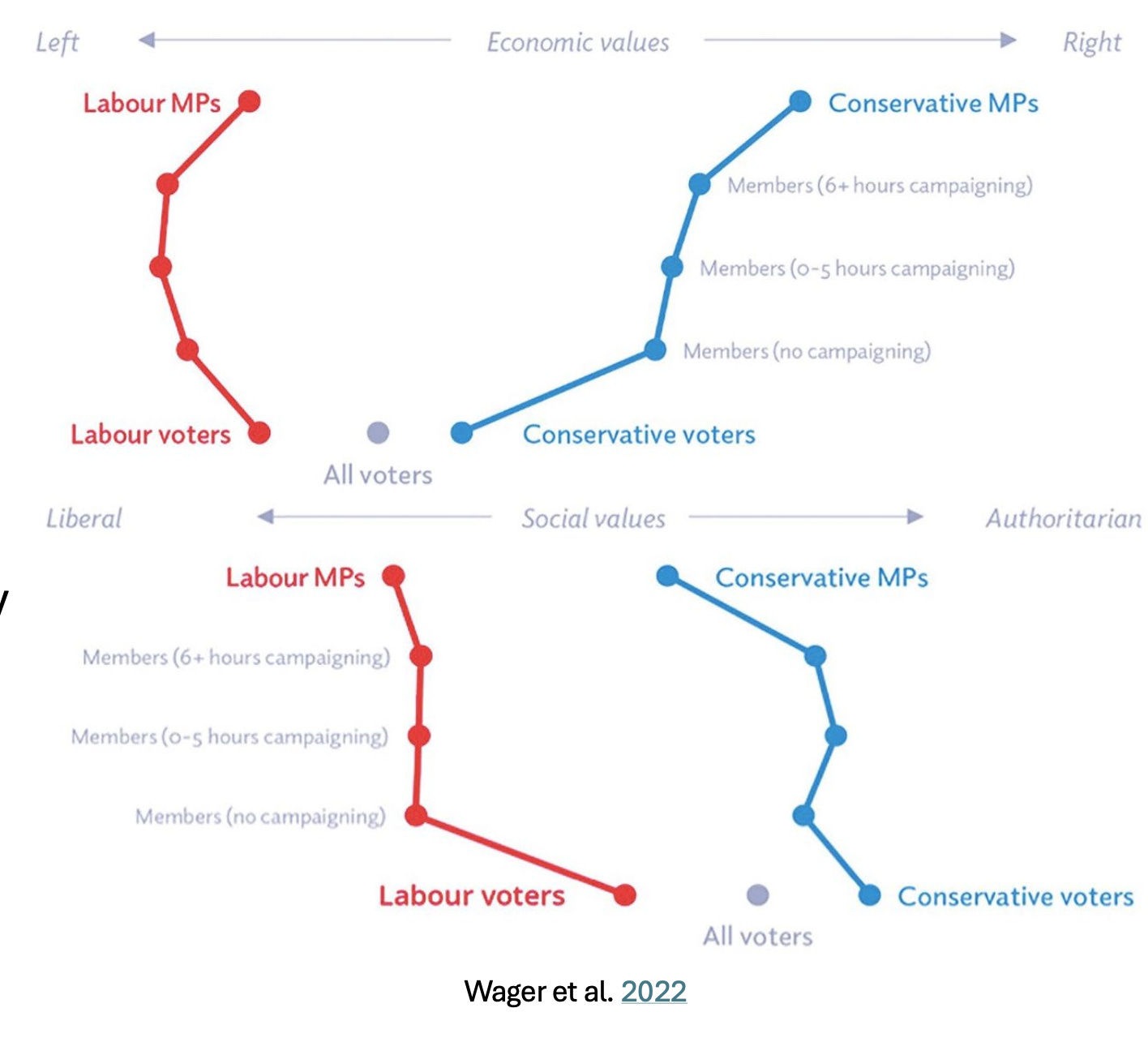

One of the core theses of my last essay was that the political tectonics are shifting: we no longer operate within a traditional left-right axis, but within a new political coordinate system—one structured around worldviews, value hierarchies, and identity questions.

The FDP needs to locate itself within this new system—decisively. That means accepting that liberalism is not some technocratic, anti-ideological middle ground (even if it’s often framed that way within the party). It is a fully fledged worldview. With principles. With values. With convictions.

In this post-post-ideological era, liberalism must be recharged ideologically—not through dogma, but through its potential to stay intellectually alive.

In Germany, liberalism is too often miscast as pragmatic reasonableness—a civic-minded middle path. But that’s a distortion. And a dangerously depoliticized one.

In truth, liberalism stands more starkly than ever against its ideological opposite: authoritarian populism. And it needs to address its own tensions—on migration, identity politics, and the culture wars. These conversations don’t belong in press releases. They belong in the party. And in its intellectual orbit.

What’s needed is a real culture of debate. One we’ve lost—out of fear of conflict, deference to the party line, or just plain intellectual laziness. We need to relearn how to argue. Yes, it’ll be painful. Maybe it has to be. Because only from friction comes fire.

Historically, liberalism has always been an intellectual adventure. And a liberal party needs to embody that again: openness without blinders, curiosity without taboo, avant-garde without elitist jargon. Back then, that happened in small but vibrant liberal blogospheres. Today it could be Substack. But if most party members don’t even know how to subscribe to a newsletter… well, that’s a training issue too. (Told you: talent development. lol.)

§6—Free Yourself from the Rhetoric of Responsibility

The FDP was voted out of the Bundestag with 4.3%, is polling at around 3%, and holds seats in just a handful of state parliaments. Yet its rhetoric still often sounds as if it’s about to form the next federal government. This level of self-importance isn’t just outdated—it’s delusional. We are an extra-parliamentary opposition. And not for the first time.

Of course, liberalism has always had a hard time in Germany. In a society shaped by Hegelian statism and Heideggerian humility, freedom-loving troublemakers rarely have an easy run. But that could be our edge. And if we finally let go of our Kantian obsession with reason, we might just break free from the German within Germany.

Because who’s going to wake Germany from its political sleepiness? Right now, maybe what this country needs is a bold, dreaming, radically subversive avant-garde of liberty. And without parliamentary constraints, liberals can afford to be loud and to overstep.

But that also means shedding our polished, state-supporting, Instagram-ready aesthetic and finally entering the age of authenticity. Our communications too often feel corporate, smooth, sterile—and ultimately fake. No wonder even Christian Lindner is starting to feel like a rerun. Our single-lane communication strategy has run out of road.

No, I’m not suggesting we go full “dark liberalism” à la Javier Milei. But a little carajo—¡Viva la libertad, carajo!—might do sleepy Germany some good.

Instead of yet another Facebook post from FDP Hintertupfingen showing a group photo from some backroom meeting, we should empower the most creative, cheeky, clever, and yes, weird defenders of liberty to become its storytellers. It doesn’t need to be glossy—in fact, it shouldn’t be. Let it be raw, real, and rough around the edges. Let it go too far. Because honestly, who expects a splinter party to deliver sober policy papers?

§7—From Orientation to Execution: After the First 100 Days

Back in §1, I argued against rushing into action. Start with deep, honest, structured analysis. But eventually, things have to move. Analysis is no excuse for inertia.

Thankfully, realpolitik has built-in pressure points. One of them is the election calendar. And that’s the opportunity: used well, this reality check can become a real-time feedback loop—for party development, strategic direction, and personnel choices.

Not everyone in today’s leadership circle needs to be part of the team that takes liberalism into the future. It’s perfectly fine to help close the gap to the breakaway group without being the one to sprint to the finish. Anyone stepping up for the liberal cause during this difficult moment deserves respect. But that doesn’t mean they’re automatically fit for a central role in FDP 2029. We need that level of honesty.

What we do need as a kickoff is a symbolic, high-energy launch. Not a classic party convention (side note: that whole concept needs a rethink anyway), but something with momentum. No plenary discussions, amendment debates, and procedural bickering—but a clear presentation: vision, positions, people, and a renewed brand.

In a culture of experimental politics and openness to outcome, no one expects a fully polished masterplan. But a Draft FDP 2029 would be a start! More pitch than plan, more prototype than product. The good news? We can test it immediately—in Baden-Württemberg.

The upcoming state election there is the perfect laboratory. A retooled FDP can demonstrate whether its new direction resonates with key audiences—or whether the awkwardness continues. And if something goes wrong? No big deal. The goal is 2029. That’s the benchmark. Everything before then is testing, learning, improving … and starting again.

That’s the mindset shift we need now.

Instead of always needing to be right, we need to learn how to want to win.

And with that, I’ll wrap up today’s essay. As usual, this is a set of raw thoughts—a draft for discussion. Many of these ideas need more thinking, more disagreement, more dialogue. I’d love exactly that.

One final note, as a plea to the new leadership: In the coming weeks and months, we’ll see a wave of proposals for structural reform. Many will be well-intentioned. But the core question of the Phoenix 2.0 project remains: Will this help help us to win again?

All well-meaning grassroots reforms aside—they’re only meaningful if they actually help us win.

That has to be the guiding principle.

Because I, for one, want to win again.

Sven Gerst, May 2025

As always, such shifts are gradual and often contradictory. The global social democratic crisis showed this—survived only by pivoting toward new constituencies (e.g. urban, progressive voters over traditional labor). But social democracy now plays a supporting role in this new ideological landscape.

As always, such shifts are gradual and often contradictory. The global social democratic crisis showed this—survived only by pivoting toward new constituencies (e.g. urban, progressive voters over traditional labor). But social democracy now plays a supporting role in this new ideological landscape.

So dunkel diese Zeit für einen freiheitsliebenden Menschen auch sein mag, sie wirkt auch als Magnet für Besserwisser, zu denen ich mich mit einigem Stolz selbst zähle, Opportunisten und natürlich für nun zurückkehrende ursprünglich vergraulte Anhänger. Aus dieser bunten Mischung ergibt sich dann vor allem das, was wir aktuell betrachten können: Flügelkämpfe um die Deutungshoheit über die Ausrichtung einer, nein, DER liberalen Partei: nämlich der einzigen liberalen Partei, die jemals in der Bundesrepublik bundesweite Bedeutung erlangt hat – und somit über den wahren Begriff des Liberalismus. Diese reinigende Entwicklung ist dabei nur zu begrüßen, da sich die FDP in den letzten Jahrzehnten nicht nur thematisch stark verengte und ihrem eigenen Programm aus übergroßer Machtgier und lupenreiner Prinzipienlosigkeit heraus den Rücken kehrte, sondern sich durch das Abhalten störfreier Jubel-Parteitage jeglicher programmatischen Dynamik entledigte.

So dunkel diese Zeit für einen freiheitsliebenden Menschen auch sein mag, sie wirkt auch als Magnet für Besserwisser, zu denen ich mich mit einigem Stolz selbst zähle, Opportunisten und natürlich für nun zurückkehrende ursprünglich vergraulte Anhänger. Aus dieser bunten Mischung ergibt sich dann vor allem das, was wir aktuell betrachten können: Flügelkämpfe um die Deutungshoheit über die Ausrichtung einer, nein, DER liberalen Partei: nämlich der einzigen liberalen Partei, die jemals in der Bundesrepublik bundesweite Bedeutung erlangt hat – und somit über den wahren Begriff des Liberalismus. Diese reinigende Entwicklung ist dabei nur zu begrüßen, da sich die FDP in den letzten Jahrzehnten nicht nur thematisch stark verengte und ihrem eigenen Programm aus übergroßer Machtgier und lupenreiner Prinzipienlosigkeit heraus den Rücken kehrte, sondern sich durch das Abhalten störfreier Jubel-Parteitage jeglicher programmatischen Dynamik entledigte.